Throughout the process of constructing the 34th Bienal de São Paulo, its curatorial team, participating artists and guest authors will send out letters with open dialogues that directly and indirectly reflect the development of the exhibition. The text below was written by the guest curator Francesco Stocchi.

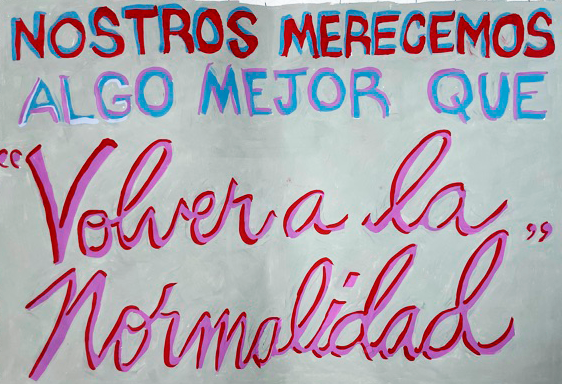

To choose utopia, as the poet Thiago de Mello did, one must believe in a better, optimistic future. The Covid-19 crisis we are currently going through has imposed a forced and arbitrary halt to the conception of a future, which is now even more uncertain, blurred and always shifting. But if we cannot look forward without getting dizzy, perhaps the current pandemic is an invitation to take a sharper look at the present. Thinking about the present, thinking about the current dramatic present, is a basic instinct, rather than a duty. Succeeding, however, is such a difficult undertaking that it seems almost impossible. The present is the result of our history, a set of personal, national, and continental histories that cannot be easily summarized. After the rise and collapse of Marxism — the last totalizing philosophy to have experienced worldwide success and diffusion, involving the intellectual and the worker, ruler and oppressed, privileged and victim — no theory or theorist has proved capable of providing a clear system of ideas that could convincingly describe the eternally mobile and circumstantial absolute that is the present.

The present, the here and now, has been accepted as a state of emergency, exceptional, urgent; in fact, life cannot and must not be postponed until tomorrow. Kierkegaard spoke of a moment, or a now, and in every religion, the "conversion" of one's whole life has always been embraced as commonplace. But moral and religious conceptions are always as peremptory as they are oscillating and paradoxical: is the truest life now or in the future, in this life or the hereafter? It is possible, and even utopian in itself, to think of this constrained time as an invitation to take an interest in the present moment, to define it, to look for its flaws, its hidden existences. Revisiting the present in order to better inhabit it necessarily implies looking back; for the moment our horizon seems on hold. Here, in this moment, as I am writing and as you are reading, we are products of a past history. Which history? Is there only one? There is, of course, the history imposed by a certain tradition in search of domination: an official history, which we have been fed since school and is anchored in the deepest recesses of our consciousness as being unique and true, without any possible discussion. Yet, there cannot be only one history for there are as many histories as there are living people. Carlo Ginzburg, a pioneer of microhistory, has made it his life's mission and struggle to bring the flaws and hollow stories of official history to light, the anecdotes that have gone unmentioned in this machine of time and memory.

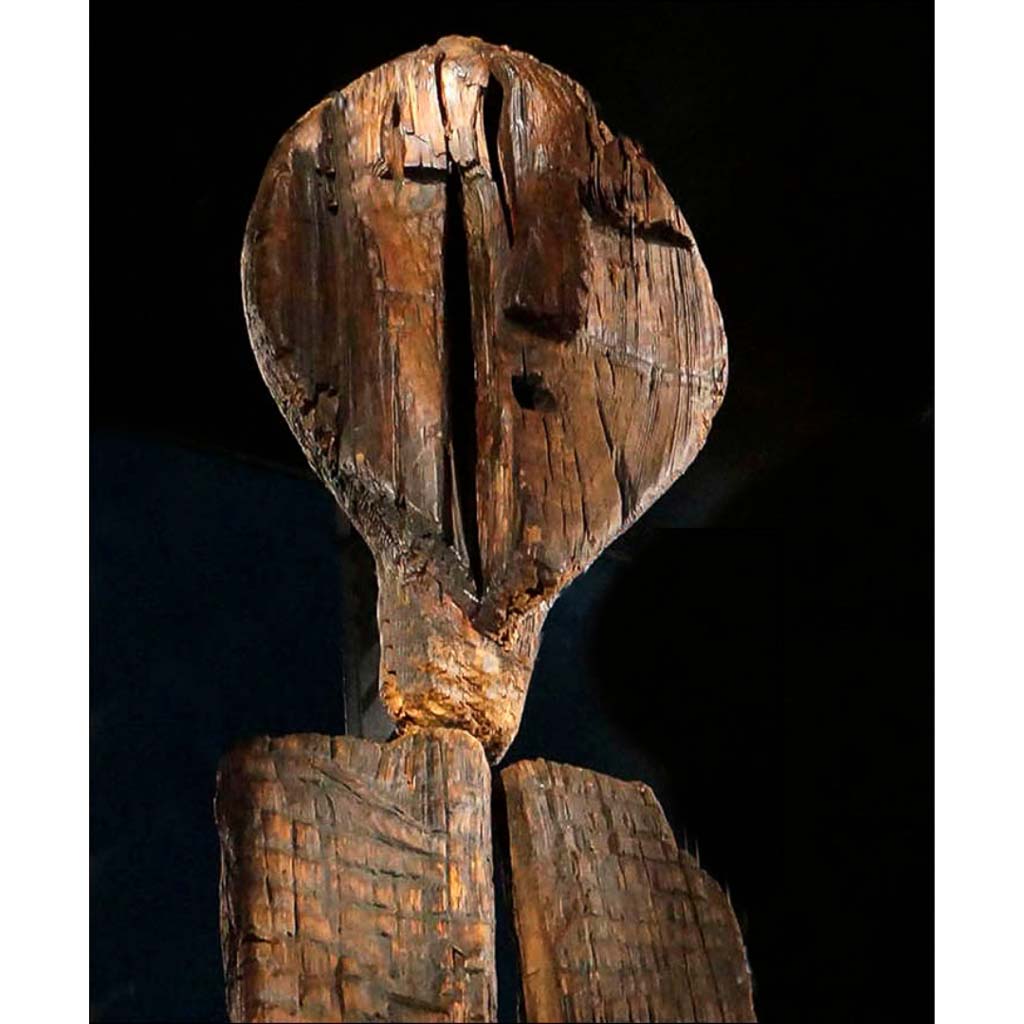

Eight human faces scattered among geometric patterns, each bearing slits for eyes that peer, not entirely benignly, out of the front and back surfaces. Renamed the “Shigir Idol,” this object was found in a peat bog in 1890, and for a long time, the dating of this wooden sculpture was under scrutiny. Recent tests using advanced technology yielded a remarkably early origin date of roughly 11,600 years ago, a time when Eurasia was still transitioning out of the last Ice Age. The sculpture is more than twice as old as the Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge, as well as, by many millenniums, the first known work of ritual art. This surprisingly early dating makes the find the earliest monumental wooden sculpture in the world. It has no direct parallel, which hinders the interpretation and contextualization of this finding. Thomas Terberger, an archaeologist and head of research at the Department of Cultural Heritage of Lower Saxony, in Germany, noted: “Ever since the Victorian era, Western science has been a story of superior European knowledge and the cognitively and behaviorally inferior ‘other.’ The hunter-gatherers are regarded as inferior to early agrarian communities emerging at that time in the Levant. At the same time, the archaeological evidence from the Urals and Siberia was underestimated and neglected.” This sculpture and the recent studies concerning its dating challenge the ethnocentric notion that pretty much everything, including symbolic expression and philosophical perceptions of the world, came to Europe 8,000 years ago by way of the sedentary farming communities in the Fertile Crescent.

The present is so present and mobile that any effort to fix it can only obtain limited and partial results. Once our certainties are undermined, both present and future utopias will become necessary tools.

![View of the sculpture of the series Corte Seco [Dry cut] (2021), by Paulo Nazareth during the 34th Bienal de São Paulo. Commissioned by Fundação Bienal de São Paulo for the 34th Bienal de São Paulo](http://imgs.fbsp.org.br/files/81b3a05327e8559c64fc5cda09f3e1f8.jpg)