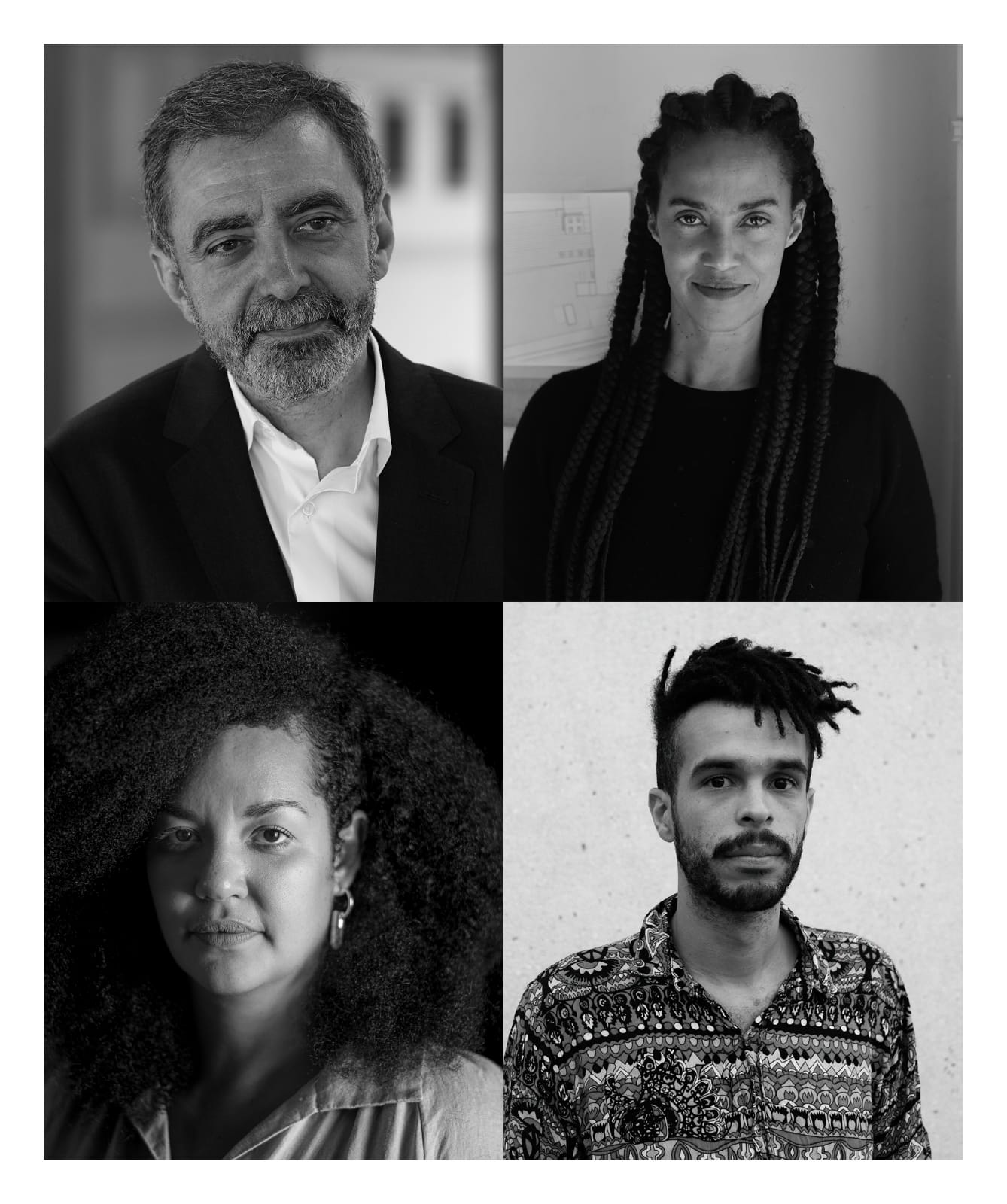

Throughout the process of constructing the 34th Bienal de São Paulo, its curatorial team, participating artists and guest authors will send out letters with open dialogues that directly and indirectly reflect the development of the exhibition. The text below was written by the Elvira Dyangani Ose, guest editor in collaboration with The Showroom, London.

Doc: Of course, there is a word that designates this body, and that you can use to call me, to talk about me, that is clear. But at the same time – and this is what captivates me – here we arrive at the crucial center – I’m also the one that escapes the name – that is my job, my task, it is what I’m called upon to do: to create uncertainty. To embody the margin. Z: Is laughter an expression of uncertainty? Doc: It is absolutely an expression of a certain limit. It shows that limit, by crossing it.

Brandon La Belle, “Interview with a Clown”

(Correspondence #9, 34th Bienal de São Paulo)

This is it.

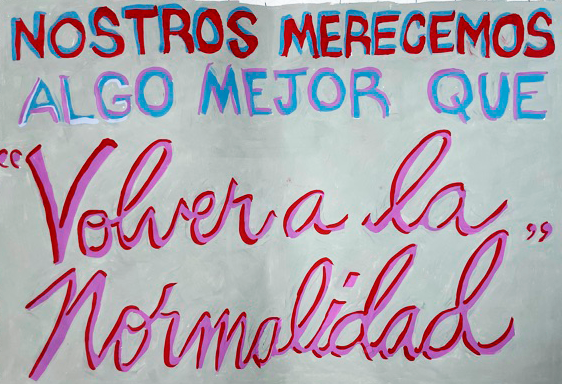

For our generation: those of us inhabiting cities in the West, where wars or conflicts occur in a faraway land. Those of us living in the Global South, where politicians seem to respond to a parallel dimension, whilst the communities they vow to serve are no longer afraid to take to the streets to claim their rights within this vividly experienced dimension. Year-long protests in Hong Kong, the Estallido social in Chile and marches against the dispossessions in Sheikh Jarrah in occupied Jerusalem are just three cases in point. Those of us waking up to dystopian political regimes, like those carried out by nation-states leaders such as Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán and Boris Johnson, it’s reminiscent of a sort of operetta, only before seen in Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy. Those of us who contend the demilitarisation of borders and the restoration of the human condition to all human beings. Those of us exhausted by famine, environmental devastation, social inequality, oppressive neoliberal governments and structural racism. Those of us worldwide whose breathing stopped – for a few seconds – both literally and metaphorically the evening of May 25th 2020, and since then have claimed resolution and punishment for murders we did not witness.

For us, whose future was postponed for a few months during that year, giving us the chance to own it – or, at least, in our imagination – to reinvent it. For all of us, this pandemic has been and will be a defining moment.

Under these conditions of possibility, the formulation of the 34th edition of the Bienal de São Paulo occurred. And, as such, there was no escape from reality. The project was conceived as an analysis of the speculative nature of art as a field of knowledge and experience production. As such it prompted to claim exhibition-making as a methodological approach to vernacular aesthetics and forgotten epistemologies, holding space for the artists’, curators’ and authors’ responses to it. It aimed to generate readings and interpretations of artworks under different conditions of display, including the physical exhibition throughout distinct spaces of the pavilion, as well as other platforms such as publications and partnering venues. With such premises in its inception alongside the evidence of a world at the edge of a new medical, social, economic and political paradigm, this exhibition could not be – should not be – based on the same prerogatives that typically would have involved a project of this magnitude.

Of course this was not the only large-scale art event affected by the unique conditions of our time. However, whilst some international events proceeded with a barely IRL – in real life – public, others tried to catch up with global audiences online. We’ve witnessed projects reinventing formats, at times readapting them to the dissolution of the “here and there.” This edition of the Bienal continued its journey with existing mechanisms – exhibitions in various venues in the city – and new platforms across the digital world in order to remain both in place and in the moment – attached to a reality forever more and more a part of the rest of the world. The truth of the matter is that whilst the world was getting out of the first and second Covid-19 lockdowns, terrifying news from Brazil continued to report daily deaths equivalent to the falling of transcontinental aeroplanes. But that did not restrain poetry – reality did not stop art or its displays – at least for some time. And that scission in communal temporality – from that initial portal that Indian author Arundhati Roy so beautifully narrated as defining the pandemic – became even more pertinent than the prerogatives of the curators, the framework under which the exhibition, but also the publication that we hope you will read, was formulated.¹

The volume contains responses to that epic, unprecedented time. As the curators and the rest of the team embarked on a Bienal edition like no other, we collectively decided we could not produce the usual catalogue. We needed to capture the essence of the moment, and harvest something that would overcome the present-ness of the matter and its unavoidable consequences. Thus in addition to images referencing artists’ works, biographies, essays and dialogues, we requested other sorts of material: images representing an artist’s practice in their own eyes – at times words or artworks of other artists – and visual references offered by the curators for a representation of the un-representable. There were tons, more than the ones included here, I am afraid – almost impossible to reproduce or financially unreachable. Many were incredibly vivid, priceless. Material for another book, for another time.

To what was ultimately gathered we added extraordinary contributions, conversations, poems and pamphlets. We offer you the chance to read and see this material from multiple vantage points and terms embedded in this kaleidoscopic set of imaginaries. They echo the observations that writer and PUC-Rio professor Ana Kiffer makes palatable in her reading of the archive and art display as “moving away from the concept of a gathering of objects of curiosity, or visions of beauty,”² and becoming a “sort of attic of the future, whose function is to shelter what should be born, but is not here yet.”³ In this respect, I almost imagine the central staircases and corridors of the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion as strips of an analogical film, towards which the physical materiality of the works add a reformulated and augmented reality – or a version of it, anyway. The complex beauty of the works on display, the assertiveness of their claims, and the profound debt they pay by giving visibility to certain stories and agents, is translated into these pages in a number of ways from visual presence to critical interpretation.

The statements are subtle entry points to some of the curatorial frameworks and narratives that audiences will encounter in the exhibition space. The correspondences by curators, artists and writers take us back in time to the germinal seeds of the project. These letters written amongst us have served to make public the exhibition’s processes and discussions over the past two years. A number of images will be familiar to those who have engaged with Tenteio, the second publication of the Bienal, which introduces the list of participating artists through an unintended visual essay. Tenteio’s images are here displaced and featured in reference to other possible nuances – visual and beyond. The publication is also an exercise of returning to a single plane, maintaining aspects of a three-dimensional visual language throughout the Bienal and its partner venues ultimately formulated as a mediation – an institutional framework – as its author, artist Vitor Cesar, observes in his Correspondence #11. Overall, the tone of book is at times sombre, at times evocative – but always engaging, overtly political.

One could argue that the Bienal format proposes an exercise of art history writing, in which a draft of possible episodes of a speculative History of Art are narrated. A draft that if created with a certain sensibility and blended with the immediate context, offers local entrepreneurship – its agents and institutions – the proper dose of international counterparts. It should put in the value of human capacities and financial means so that some green can grow after the event has passed by. It should reflect upon something fundamental to that particular ecosystem, and relevant to the field of art at large. For the audience, it should be unique and memorable, yet accessible and familiar – as I believe this edition of the Bienal to be. Some of the multiple avenues we explore in this volume will be disrupted, discarded or augmented in the exhibition, but make no mistake: they will just be other interpretations and dialogue – as opposed to the interpretation, per se. They are the expression of a certain definition, a certain narrative, a certain limit. As Doc, the Clown from Correspondence #9, notes, “it shows that limit, by crossing it.”⁴ All is permeable, mutable, ever-changing.

Not so long ago, I was reading a reflection on the myriad of defining stories that would have taken place in the last eighteen months. The number of occasions someone would have understood in the suspension of time that we experienced: the possibility of amending, reinventing or changing their present – and possibly their path to the future – once and for all. How many New Year’s resolutions were there, how clairvoyant the conclusions to Groundhog Day journeys that would have filled notebooks and diaries. Leaps of faith, farewell hugs, moments of impossible nervous laughter, frustrations and overwhelmingly heavy silences. And then, I remember when I was a child. For a while between the mid-1970s and the end of the 1980s, we used to travel every two years from one Spanish city to another. A black family of five, starting a home in every new place. My mother making the effort of adjusting rooms to what we did not know at the time was called nostalgia. Reflecting on this from the perspective of an adult, it was hard.

For a child, for my brothers and I, it was an imposed and extreme change to our world. With the first and second moves, one suffered. Those initial ruptures had to do with loss, with what is left behind; lingering to what was no longer there, no longer possible. Then, not so long after, these changes of universes – new school, new neighborhood, which for a 7 or 13-year-old girl were almost everything – became a strange platform for fabulation, for newness. I cannot speak for others, but for me it became an opportunity for reformulation, for change, for embodied renewal. A strange pursuit evolved for changing the aspects of things that would have not worked in previous cities, that would have gone wrong with this or another friend.

“It is harmless” – I thought.

Of all the possible me’s that could have been impersonated, I decided for the transient one, the one who could not be labelled or fixed, that offered herself a constant right to be one and multiple, unique yet permeable, open to change, committed to endless transformation. It was somewhat of a relief. That feeling that nothing was there forever, that all was mutable – certainly, happiness was, and thus so was sadness, and fear.

¹ This correspondence also introduces and makes references to the catalogue of the 34th Bienal, to be released at the exhibition opening, on 4th September.

² Ana Kiffer's quote from the 34th Bienal de São Paulo catalogue

³ Achille Mbembe, Brutalisme

⁴ Correspondence #9, by Brandon LaBelle

![View of the sculpture of the series Corte Seco [Dry cut] (2021), by Paulo Nazareth during the 34th Bienal de São Paulo. Commissioned by Fundação Bienal de São Paulo for the 34th Bienal de São Paulo](http://imgs.fbsp.org.br/files/81b3a05327e8559c64fc5cda09f3e1f8.jpg)