Throughout 2020, through letters like this, the curatorial team of the 34th Bienal de São Paulo will make the reflections on the exhibition's construction public. This seventh letter was written by Ruth Estévez e Carla Zaccagnini.

RE - We decided to title the Bienal Faz escuro mas eu canto (Though it’s dark still I sing). From the beginning I thought it was a fortunate choice, especially because of the difficulty in understanding what “it’s dark” may mean. It’s dark at this very moment, it’s permanently dark, it’s getting dark… Is it something positive or negative? Darkness is negative and singing positive? That division didn’t quite work out for us.

Each of us had a way of understanding “I sing”, and suddenly “it’s dark” stopped being relevant. In my case, I could only see it as meaning “I fight”, I continue, whatever may happen. In many moments I have resisted an understanding of the title as simply: even though it’s dark, we must sing… or, there are other ways of singing, or, even, that we must respect the diverse ways of singing. Or that singing is, above all, a celebration.

I imagine if we were able to split the title in two we could even organize two completely different projects.

It's dark I sing

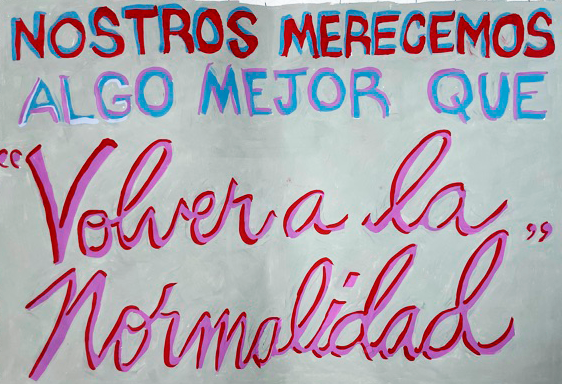

CZ - I like how you divide the title in two, leaving out the adverbs, the connectors. For a moment I thought we’d need to substitute those words for others that don’t imply an opposition between darkness and singing. Rather than “though it’s dark, still I sing”, something like “it’s dark, so I’ll sing” (or “it’s dark, so let’s sing”). The singing becomes even more necessary in the darkness, it is not about singing despite the fact that it’s getting dark, but singing precisely because it is a way of facing darkness.

Many animals sing, and don’t do it to celebrate the present or for faith in the coming days. They do it to mark the position they occupy and the territory around them. They do it to find companions that may recognize that singing. They do it because that’s their way of actively constructing the future, through the next generations.

RE - Yesterday you sent us all a video of an Argentinean punk band called 2 Minutos that proposed that everybody sang a song at a specific time, during a quarantine that inevitably hinders dialogue. Singing has become some sort of palliative, in a society in which orality is more relevant than ever, as there’re so few opportunities to use our body. In a moment when the frontiers have become our own skin, the voice is a possible form of relation. Singing is an act of re-cognition, so that they know you are really still there. Some sort of groping.

I was watching a chapter of the television series Chernobyl, an invisible disaster. In one of the scenes an elderly woman is milking a cow at her farm when the military orders her to leave because of the radioactive levels in the area. It’s 1986, when the former USSR soldiers evacuated a radio of 30 km around the nuclear plant. The woman, without raising her eyes, begins to tell the soldier her story, which is actually the history of the USSR for a century. All the others have died, and only she remains. After finishing, she says to him: “I’ve gone through it all, and I’m still here. Do you think I’m going to leave because of something invisible?”

CZ - An invisible threat, on the one hand, allows us not to believe in it. It’s easier to doubt the existence of ghosts we don’t see than to stop fearing those that are mere appearance: costume, makeup, chain sound effects. On the other hand, when the threat is invisible, switching on the light or closing your eyes won’t help. Neither running, because the invisible or microscopic threat may be anywhere, or everywhere at the same time. Or, worse, we may carry it inside us. Carry it around and transmit it without being aware. We don’t only have to be careful about any person and her traces, we also have to protect the others from ourselves. Facing the current threat, that old lady would be safe with her cow until the soldiers’ arrival.

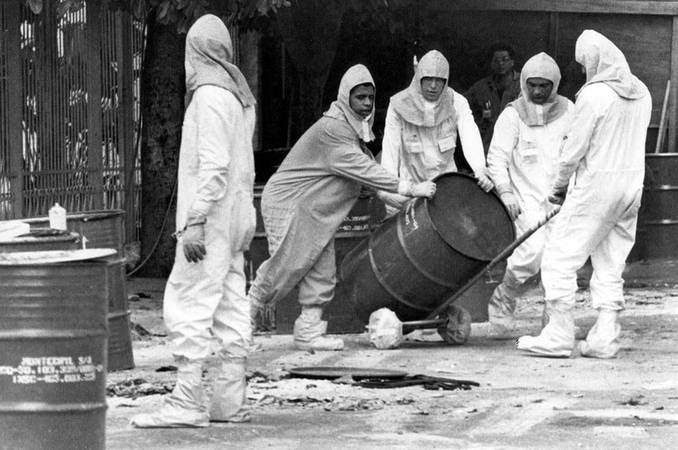

The following year, 1987, the biggest radioactive accident outside a nuclear plant took place in Goiania, at 200 km from Brasília. The origin of the disaster was an obsolete radiotherapy machine, forgotten in an abandoned public building, found by chance by two informal cardboard collectors and sold to a scrap merchant, who, inquisitive, hammered the capsule open and liberated the Caesium-137. The accumulation of small, almost domestic, somehow naive errors, resulted in hundreds of deaths and tons of atomic waste. Brazil. The dust, which had a blue glow in the dark, dissipated, not due to its invisibility, but because of a beauty never seen before.

There’s almost no distance between invisibility and excessive visibility. One of the main clandestine presses during the military dictatorship in Argentina functioned in a property where there was also a small rabbit farm. The press occupied the back of the lot, behind a false dividing wall. It could be accessed through a hidden passage underneath the rabbit cages. The opening mechanism was on full view, the cables apparent, untidy, as if they’d been forgotten. The engineer built it that way, with the conviction that “nothing hides better than an excess of evidence”, as he had learnt from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Purloined Letter.

RE - Excess of evidence… that may be the problem…

In these past years many things have taken place, one after the other. Among them, of course, physical evidences, maybe more physical than ever before (the fires in the Amazon, the revolts in different parts of the world, the global pandemic...). On the other hand, we began the Bienal with a methodological premise, trying not to put forward a specific theme. It’s as if we had created a template in which the different pieces could fit in, but every time the board was full, a sudden gust of wind blew and pushed everything onto the ground.

Suddenly, an invisible virus arrives, with devastating consequences, and we forget at once about all the empirical tests that took place before. Neither ghosts nor gusts of light, just mere facts. I think we don’t even have to worry about leaving the cables on view to expose the mechanism and distract the attention towards something else. The cables are out in the open. The printing press is working in broad daylight. The evidence is confirmed. The witnesses have already spoken and their voices have been registered in all the possible formats. The ghosts don’t even bother turning transparent. Everything has been laid on the table for a while now.

The problem is a matter of timing. If they switch some of our lightbulbs off for a short period of time we go mad. If they tell us the blackout will come in some decades we remain calm, ignoring the evidences.

CZ – “Seeing is believing”, they say, don’t they? As if the blind were always unwilling to believe. I always imagined the inside of a blind eye as a completely dark room, a room with blackout curtains like the ones that are used in the north, to compensate for the endless summer days. How necessary a dark place may actually be!

In the title, what I was most worried about was the word “dark”, the association of darkness to what is difficult, sinister (which not by chance relates to the left), sad, uncertain, evil; an association that has been constructed during centuries. It is not just about singing, but rather about daring to look at the shadows, getting used to the absence of light and seeing all that exists within darkness.

Helen Keller was a writer, a key activist in the struggle for universal suffrage and an advocate of revolutionary unionism. Blind and deaf since before reaching two years of age, when she went to the top of the newly inaugurated Empire State Building and was asked what she thought of the view, she replied with a letter. In it, she writes: “As I now recall the view I had from the Empire Tower, I am convinced that, until we have looked into darkness, we cannot know what a divine thing vision is.” And further: “the strange grass and skies the blind behold are greener grass and bluer skies than ordinary eyes see. […] For imagination creates distances and horizons that reach to the end of the world. It is as easy for the mind to think in stars as in cobble-stones.” Everything fits within darkness.

The letter ends by saying that she – perhaps like us – is “one of those who see and yet believe.”¹

¹ Helen Keller, letter to John Finley, 13 jan. 1932. Available at: https://archive.org/stream/newyorkthathelen00kell/newyorkthathelen00kell_djvu.txt. Accessed in jun. 2020.

![View of the sculpture of the series Corte Seco [Dry cut] (2021), by Paulo Nazareth during the 34th Bienal de São Paulo. Commissioned by Fundação Bienal de São Paulo for the 34th Bienal de São Paulo](http://imgs.fbsp.org.br/files/81b3a05327e8559c64fc5cda09f3e1f8.jpg)