Throughout 2020, through letters like this, the curatorial team of the 34th Bienal de São Paulo will make the reflections on the exhibition's construction public. This sixth letter was written by Paulo Miyada.

An “essay,” in the sense of a test. An attempt to be together with a certain idea without isolating it, but rather walking beside it, while it becomes interwoven with flows of thoughts, happenings and recollections.

This is an essay about an essay. An association of reflections about the procedural exercise of arriving closer to something through trial and error. An open format that debates the opening up of processes of learning.

Rio de Janeiro artist Hélio Oiticica lived outside Brazil during the years documented as the most violent of the military dictatorship, those which followed the December 1968 decree of Institutional Act No. 5 (AI-5). Upon his return to Brazil in 1978, he witnessed the incompleteness of the “slow, gradual and sure” relaxation of the dictatorship promised by General Ernesto Geisel: despite the decrease in attacks on politicians, activists, journalists, students, union leaders, artists, lawyers and professors, the regime’s institutionalized violence had inflamed a much older, widespread and deeper wound – the premeditated genocide of the black, poor and marginal population – and this was far from having an end.

This is an essay about an essay that was written in Latin America, where political forces and projects of power recurrently proclaim new eras of progress and civilization, which are born premature and then destined to abandonment. Where the ubiquitous form of urban and infrastructural growth is the speculative essay, rather than planning and the collective construction of the ideas of the city and the territory.

In French, essayer means “to try,” but it can also mean “to test.” In English, [unlike in Portuguese] “essay” does not spring from the same root word as “rehearsal.” In Macuxi, esenupan means “to try out” and “to train,” but it also means “to teach” and “to learn.” In Japanese, 復習える (saraeru) is equivalent to “to try out” and bears the combination of ideograms that refer to the ideas of “repetition” and “learning.”

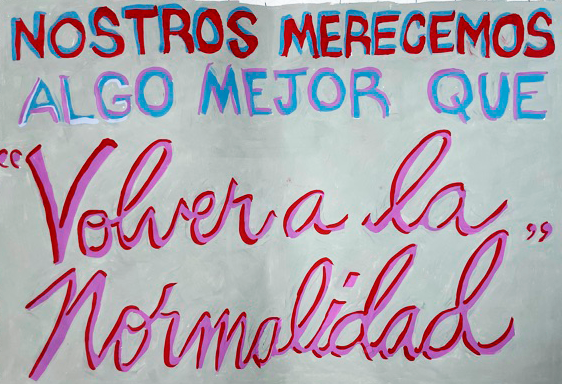

In Latin America, there is often too much 復 (repetition) and a lack of 習 (learning). The essay of development is repeated and we do not learn its lessons. Eternally emerging, nations throw themselves euphorically into new constructions and then abandon them, half ready or half in ruins, to return to their usual place as suppliers of commodities. The Olympics, the hydropower plants, the dams, the catechizations. The copper, the niobium, the brazilwood. Or, the Republic, democracy, racial integration, just before and just after economic dependency, dictatorship, slavery. Education and censorship in a Mobius strip.

In an interview made soon after his return to Rio de Janeiro, Oiticica spoke about his sadness of perceiving that he could not find more of the many friends he had left in the mid-1960s in Rio’s favela and samba scene: “Do you know what I discovered? That there is a program of genocide, because most of the people I knew in Mangueira are either in prison or have been killed.” In 1965, Hélio had witnessed at close range the rise of one of the first militias in Rio, the death squad by the name of “Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq,” whose inspiring leader was a police detective killed in a confrontation with the outlaw Cara de Cavalo, a friend of Oiticica’s who was branded as the nation’s enemy #1 and brutally executed. One decade later, he saw how much the state and para-state violence had intensified, and was one of the first discordant voices to ring out within the prevailing tone of “re-democratization,” pointing to the persistence of the massive attack on the peripheral, mostly black population.

Here, when there are monuments, they are above all those that shamelessly rewrite history in a glorious way. There are few museums about violence and conflict. Almost no learning.

It would be better to abandon those monuments and to multiply the essay/rehearsal as a verb to hold things and feel their weight. Trying out approximations and distances, juxtapositions and provisory connections to make certain clusters of relationships more evident.

In 1979, shattered by the execution of yet another friend, Oiticica conceived a “parangolé-area” called A ronda da morte [The Death Watch]. In the shape of a black circus tent, it was to have strobe lights and music playing inside, beckoning for people to come in and dance. While the festivities were taking place inside it, the perimeter of the tent was to be surrounded by men on horseback, who would ride around this area simulating a patrol. The music inside would allay the sense of imminent risk that reigned outside, directly alluding to the state of surveillance and violence that persisted despite the apparent normalization of day-to-day life.

While the first news reports about the new coronavirus in Wuhan were circulating, the summer rains in various Brazilian capital cities brought a repetition and return to things that had been previously covered over. As the urban structure of many cities had been fueled by greed, laying thoroughfares over the channeled beds of their main rivers, it took only a few of these storms for the watercourses to burst their restraints, reconstituting the original rivers on top of the streets. Just a few months later, that faraway epidemic had transformed into a global pandemic, another form of catastrophe that questions the sustainability of the way we are occupying and consuming the planet.

In 2019, we imagined that it was time for that proposal of A ronda da morte to leave the drawing boards, because the program of genocide that Oiticica talked about unfortunately persists in our country’s present reality, as seen in the asymmetric applications of law which has led to the racialization of the Brazilian penal system. There are also the death squads and the militias, which are active at the local level even while they are linked to powerful figures in the highest places. Even though the country’s social and racial stratification conceals the truth from the eyes of certain sectors of society, allowing them to continue dancing as though everything were just fine, a short trip outside of the elite districts of the state capitals is enough for one to perceive that death is still lurking about, as always.

For this reason, our plan for the series of performances leading up to the opening of the main show of the 34th Bienal had called for the last one to be A ronda da morte. It would not have been a simple process, since Oiticica’s instructions are very open, allowing for a great deal of interpretation and creating many challenges of translation to the present time. Now the situation has been intensified by the pandemic, which challenges any sort of planning and discourages crowds – especially large ones, like Oiticica wanted.

It is most likely that, once again, A ronda da morte will continue to be an unrealized idea; but the motives for this suspension allow for a reconsideration about the presence of death. On the one hand, Covid-19 burst all the protective bubbles that allowed segments of the population to illude themselves about their safety behind security cameras, alarm systems and bulletproof glass – the virus does not care about the security features offered by these devices. On the other, the behavior of certain politicians and businesspeople brutally materializes the genocidal project of the country’s construction, stirring the anguish and revolt arising from the pandemic’s multiplied effects in peripheral districts, favelas and prisons. Death is universalized as a common threat, though in reality its reach is brutally unequal. Perhaps A ronda da morte does not need to be installed in the Bienal pavilion, because it is now everywhere. Even if there is no music or the sound of horses’ hooves. The silence of the muzzled city is interrupted only by the sirens, the beating of pots and pans in protest, and by the songs that crisscross through the neighborhoods.

Another recollection: the Bahian singer and song composer Dorival Caymmi liked to repeat very simple words in his songs: beautiful beautiful; palm tree, palm tree; sand, sand; longing, longing. His restrained lyrics only presented the bare minimum to convey the subtle difference that each of the words would inevitably bear with each repetition. A difference of the same order of magnitude as between the waves that break at the seashore.

Beyond the lesson in form, Caymmi wrote a song that expresses an alternative proposal for a relationship with the territory, in which it is the humans who should learn to mold themselves to the cyclical temporality of nature, rather than shaping it with their own accumulative and linear time.

![View of the sculpture of the series Corte Seco [Dry cut] (2021), by Paulo Nazareth during the 34th Bienal de São Paulo. Commissioned by Fundação Bienal de São Paulo for the 34th Bienal de São Paulo](http://imgs.fbsp.org.br/files/81b3a05327e8559c64fc5cda09f3e1f8.jpg)