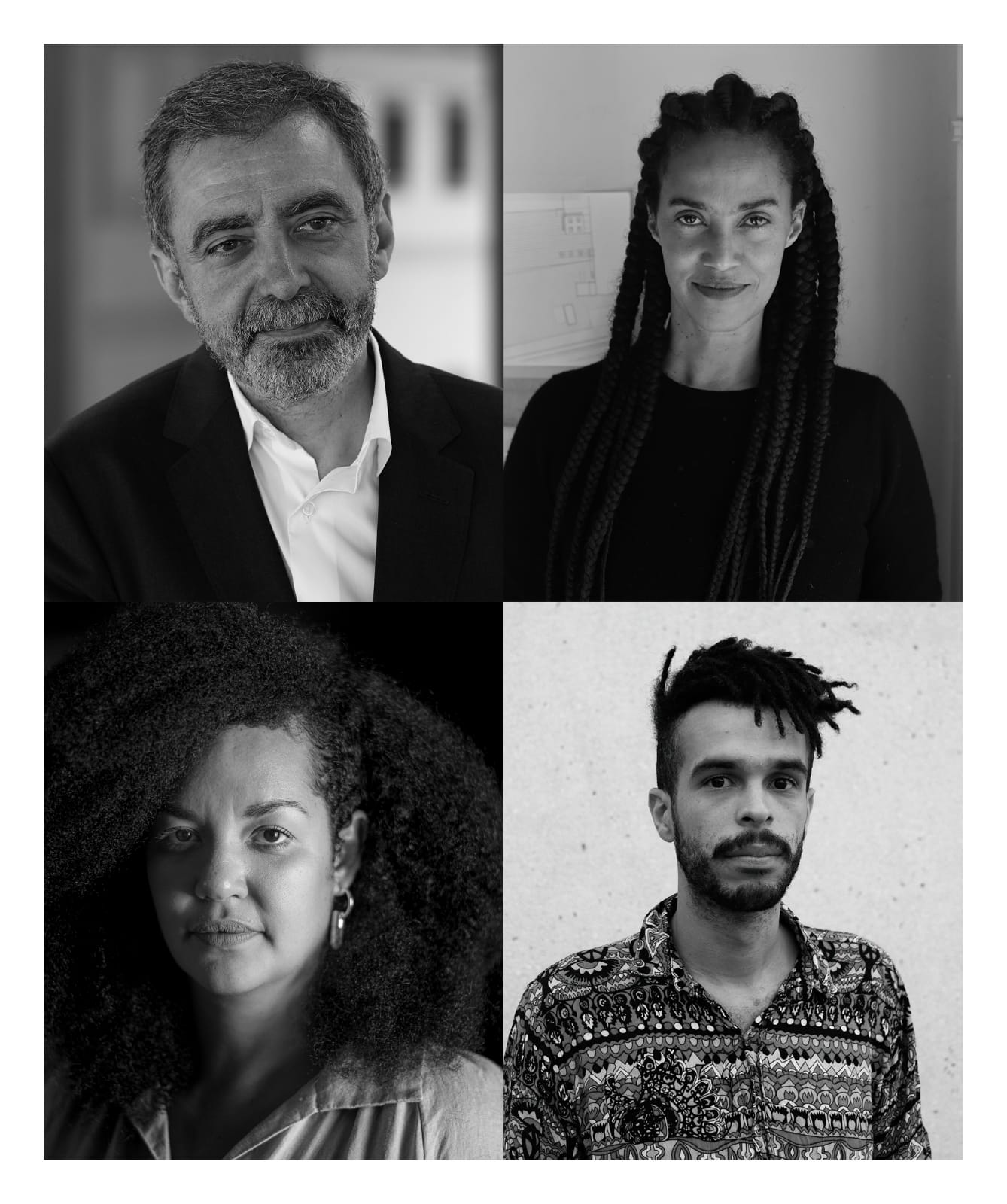

Throughout the process of constructing the 34th Bienal de São Paulo, its curatorial team, participating artists and guest authors will send out letters with open dialogues that directly and indirectly reflect the development of the exhibition. The text below was written by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, chief curator of this edition.

A few days from now, the Bienal building will once again start receiving people and artworks. Sounds and images will occupy the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion in a spaced and rarefied dialogue, made up also, or principally, of voids and silences. Édouard Glissant once wrote that “there is no absolute beginning. Beginnings flow in every direction, like meandering rivers”.¹ These words apply perfectly to a show like Vento [Wind], which acts as a turning point in the course of the 34th Bienal, in that it signals a necessary change in direction and not an interruption of movement, an end or a beginning. Glissant also spoke of echo-worlds: worlds made of echoes that, like almost everything in his poetics, transform constantly, until we no longer know where each word came from, in an incessant process of creolization and fertilization. The wind carries the echo, which is simultaneously the memory of what was said and its reverberation into the future. Similarly, Vento works as the index of this edition of the Bienal in the sense that it addresses some of the themes that will return in expanded form in the exhibition in September next year, and at the same time it refers to what has already happened as, in semiotics, the index constitutes the trace.

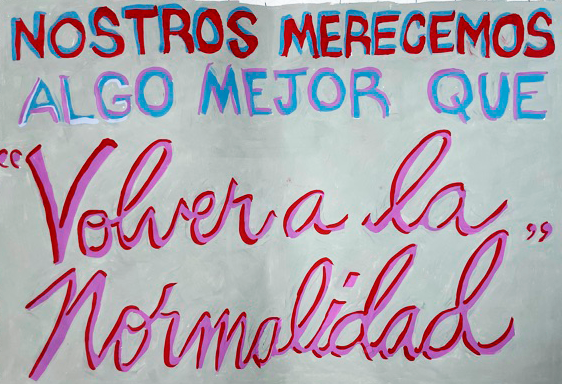

The distance between the works, many of them made with sound alone, is the most striking characteristic of this stage of the exhibition, and acts as an invitation to pay attention to things we cannot see or hold in our hands, but which have a profound influence on our lives, now more than ever. It is thus an experimental gesture, the realization of a desire to make tangible that which, by its very nature, is not: the space between things, the void that, like a mold in constant transformation, reflects and mirrors the shape of the world. We can imagine the wind is also shaped by whatever it meets on its path, and it is in this spirit of being open and permeable to what surrounds us, but also with a desire to influence the world in turn, that the show was conceived and put together. In a recent conversation with Carmela Gross, discussing the title of the 34th Bienal – Though it's dark, still I sing – Gross said something that stayed with me: "The It's dark is something that is given, but singing is something within our control. The I sing symbolizes an effort that happens through our action". A few days before, in another conversation, Neo Muyanga asked, without really expecting anyone to have an answer, what the "new image of solidarity" would be. We are used to associating the idea of solidarity with a gathering of people, perhaps in motion, bodies close to each other, so close that they become physically and conceptually one. Today, however, it's necessary to keep a distance, and not for political reasons, but for human ones: for solidarity. Neo's question is pertinent and thought-provoking in this context. And the response, perhaps, comes through song.

It's almost always dark when the Tikmũ’ũn start to sing. Their songs, some of which permeate the exhibition, summon the spirits of every thing that makes up the world, of what we can and cannot see. The Tikmũ’ũn, or Maxakali, are an indigenous ethnic group originating from a region that encompasses parts of what are currently the states of Minas Gerais, Bahia and Espírito Santo. After countless episodes of violence and abuse, recurrent since the colonial era, the Tikmũ’ũn came close to extinction in the 1940s and having been forced to abandon their ancestral land in order to survive, are today divided in villages distributed in the Vale do Mucuri. Life in the villages is organized around a rich repertoire of songs, which evoke their rich cosmology and form a catalogue or an archive of all the elements present in their lives, including plants, animals, places and objects. Many of these songs are performed collectively, and their aim is often curative. Among the Tikmũ’ũn, the act of singing is an integral part of life, because it is through song that they preserve the memories that make up the community. Each member of the community is responsible for a part of the songs, which in turn belongs to a spirit (Yãmĩy) who is summoned and nourished in the singing ritual. Together, the songs compose the Tikmũ’ũn universe, which consists of everything that these people see, feel and interact with, but also of the memories of plants and animals that no longer exist, or that remain in the places they had to flee from in order to survive. As a community, they live in the language they still practice and vigorously defend. Singing.

It's hard to imagine a more poetic, coherent and compelling metaphor for solidarity in these times: a community in danger, where each person depends on the knowledge and memory of others to keep going, for everyone's world to keep existing. The community's strength is constantly renewed in the collective naming and constructing of the universe: each set of songs is indispensable in the revival and reaffirmation of the whole. Not one of the entities in this abundant cosmos can be left behind, except at the cost of losing something irreplaceable – in a sick world, where necropolitics reigns and consolidates indifference and negligence as instruments of government, this lesson resonates with even more power. It reminds us that every member of a society is interconnected, and that the things that each of us knows and says are equally important for the common objectives we have established for ourselves. Above all, even in the challenging, threatening and dramatic times that the Tikmũ’ũn and so many other groups have gone through and continue to go through, it reminds us of the importance of not losing the will to sing. That is, even in challenging, threatening and dramatic times, of not losing the simple courage to recognize and sing about the beauty of animals, both big and small, of the fragile grass creeping up the flourishing trees, of the powerful river and the almost immaterial mist, of the sun, the moon and the stars, of the earth where we plant our feet, and of the wind.

¹ Édouard Glissant, La Cohée du Lamentin. Paris: Gallimard, 2005.

![View of the sculpture of the series Corte Seco [Dry cut] (2021), by Paulo Nazareth during the 34th Bienal de São Paulo. Commissioned by Fundação Bienal de São Paulo for the 34th Bienal de São Paulo](http://imgs.fbsp.org.br/files/81b3a05327e8559c64fc5cda09f3e1f8.jpg)